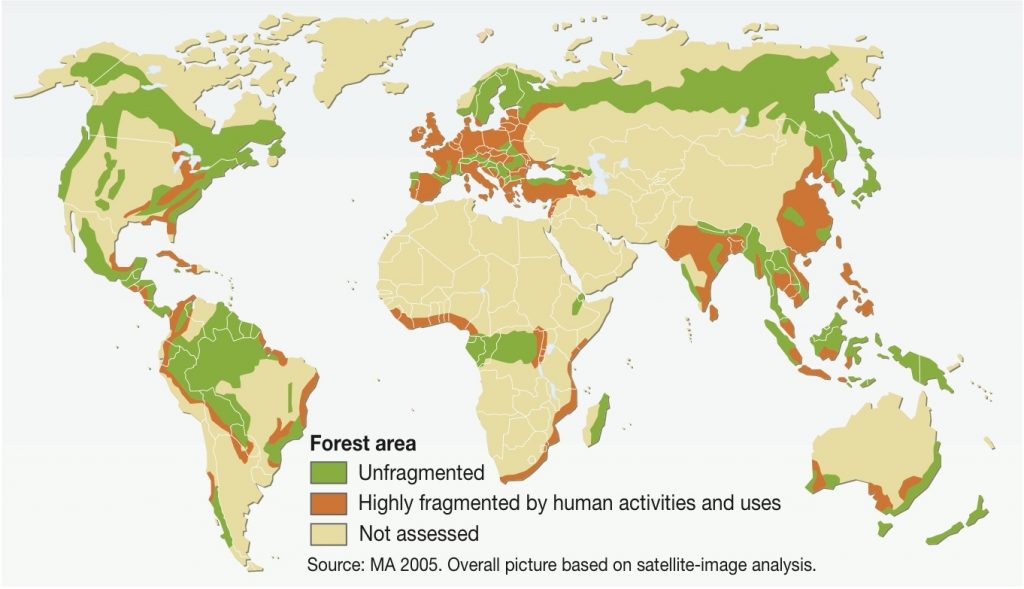

It’s a well-known fact that deforestation is happening at extreme rates! Just look at the Amazon rainforest, where 20 football pitches worth of trees are removed every minute (Carrington, 2013). These global environmental changes are associated with our topic for today: fragmentation!

.

WHAT IS FRAGMENTATION?

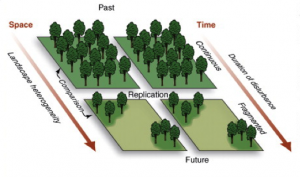

Forest fragmentation occurs when the total cover of a native forest is reduced. It is associated with anthropogenic deforestation, and leads to patchy forests and overall forest loss (Murcia, 1995) (Kupfer et al, 2006).

The isolated patches of forested habitats (remnants) in between the cleared forest cover follow the theory of ‘Island Biogeography’. Principles of Island Biogeography link forest fragmentation with biodiversity loss (Kupfer et al, 2006).

.

.

FRAGMENTATION EFFECTS ON ECOSYSTEMS

– Microclimate Change (Saunders et al, 1991)

The microclimate within and surrounding the remnant forest is altered in the following ways:

More solar radiation. This restricts shade-tolerant species and encourages the spread of new species of plants (ex. vines, secondary vegetation) and animals to occupy the forest clearings and edges.

The accompanied temperature rise alters soil moisture and nutrient availability, modifying the local vegetation. It also disturbs species interactions and animal foraging behaviours (ex. Carnaby’s cockatoos).

.

Stronger winds. Reducing the denseness of the forest leaves it more exposed to penetrating winds. That, amongst other things, changes vegetation structures and food availability for the forest communities.

Increased water flux. Fragmented forests alter the landscape through heavy water flows that erode the topsoil and transport more particulate matter across the forest cover.

.

– Isolation (Saunders et al, 1991)

Remnant forest habitats are usually left crowded, with more species than they can actually support. Therefore, over time species will inevitably be lost due to the lack of resources and space available.

Species survival will generally depend on how well they can adapt to new conditions or migrate to new areas. The most rapid extinctions will occur for species with small populations, or ones that are heavily dependent on native vegetation or large territories.

.

– Greenhouse Effect

Tropical rainforests store large amounts of carbon. Destroying them releases this stored carbon into the atmosphere and largely contributes to global warming (Laurance et al, 2002).

.

.

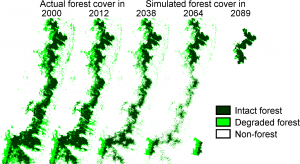

MADAGASCAR

.

Fragmentation is a major concern for Madagascar: The original extent of the eastern rainforest was around 3 times larger than what it currently is!

.

.

Its size is diminishing due to fires, illegal logging and agricultural deforestation (Ganzhorn et al, 2001).

.

.

Many larger species have been lost, and the remainder are unlikely to maintain viable populations beyond 2040. Populations of lemurs with fewer than 40 adults cannot survive. Worryingly, none of the remnant patches on the eastern Madagascar forest are large enough to maintain even such populations (Ganzhorn et al, 2001).

.

.

.

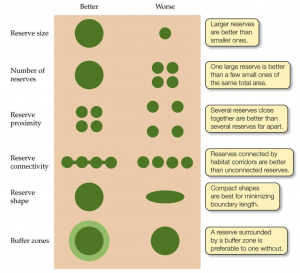

THE ONLY SAVING GRACE: CONNECTIVITY

Corridors to connect remnants have proven useful when striving to enhance biodiversity.

They can aid the re-colonisation and immigration of species, provide refuge, and help with further species interactions (Saunders et al, 1991) (Laurance et al, 2002).

The size and shape of the remnants can also affect its vulnerability to external factors:

.

Word Count: 499

.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON:

Fragmentation effects on ecosystems you can watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzf-uX6kGkk

How Madagascar is managing its lemur populations you can watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZhOyD79ymJA

.

.

REFERENCES:

Carrington, D. (2013). Amazon deforestation increased by one-third in past year. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/nov/15/amazon-deforestation-increased-one-third [Accessed 18 Mar. 2017].

Ganzhorn, J., Lowry, P., Schatz, G. and Sommer, S. (2001). The biodiversity of Madagascar: one of the world’s hottest hotspots on its way out. Oryx, 35(04), p.346.

Green, G. and Sussman, R. (1990). Deforestation History of the Eastern Rain Forests of Madagascar from Satellite Images. Science, 248(4952), pp.212-215.

Kupfer, J., Malanson, G. and Franklin, S. (2006). Not seeing the ocean for the islands: the mediating influence of matrix-based processes on forest fragmentation effects. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 15(1), pp.8-20.

Laurance, W., Lovejoy, T., Vasconcelos, H., Bruna, E., Didham, R., Stouffer, P., Gascon, C., Bierregaard, R., Laurance, S. and Sampaio, E. (2002). Ecosystem Decay of Amazonian Forest Fragments: a 22-Year Investigation. Conservation Biology, 16(3), pp.605-618.

Murcia, C. (1995). Edge effects in fragmented forests: implications for conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 10(2), pp.58-62.

SAUNDERS, D., HOBBS, R. and MARGULES, C. (1991). Biological Consequences of Ecosystem Fragmentation: A Review. Conservation Biology, 5(1), pp.18-32.

Recent Comments