The Brazilian Atlantic rainforest is made up of some of the most important ecosystems on earth (Magnago et al., 2014). It supports species that are not found anywhere else on the planet (Ribeiro et al., 2009). However, the rainforest is not the vast expanse of green canopy that you might imagine.

In fact, deforestation has divided the landscape. Now, more than 80% of the remaining forest is made up of fragments with an area of less than 50 hectares (Ribeiro et al., 2009). Almost half is less than 100 metres from its edges (Ribeiro et al., 2009).

The situation in the Brazilian Atlantic rainforest is not uncommon. Due to fragmentation, more than 70% of the world’s forests are now within 1 kilometre of a forest edge, impacting rainforest ecosystems across the globe (Haddad, 2015).

WHAT IS HABITAT FRAGMENTATION?

Habitat fragmentation is the division of a habitat into increasingly smaller and more isolated pieces (Haddad, 2015). In rainforest ecosystems, this is done through deforestation. Fragmentation effects the entire ecosystem, by reducing forest area, increasing isolation and increasing forest edges (Haddad, 2015).

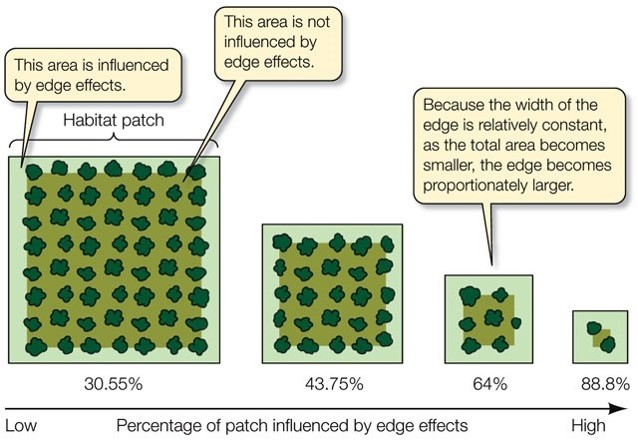

EDGE EFFECTS

Edge effects are the ecological changes that occur at the boundaries of these habitat fragments (Laurance et al., 2016). They can include (Laurance et al., 2016)

– Increased wind damage

– Changes in temperature and humidity

– Increased flooding

These effects may make the environment along the edges of fragments unsuitable for certain species, making their available habitat even smaller (Turner, 1996).

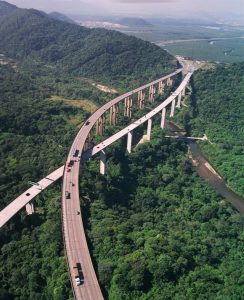

THE HABITAT MATRIX

The landscape surrounding forest fragments is referred to as a “matrix” of habitats (Haddad, 2015; Gascon et al., 1999). The matrix plays an important role in acting as a selective filter for the movement of species between fragments (Gascon et al., 1999). Animals that cannot survive the matrix will be unable to move across fragments. This not only makes the animals themselves at risk of decline, but if they play a role in seed dispersal (by transporting plants’ seeds in their faeces, fur or feathers) plants will also be at risk.

But, it is not all bad news: studies have found that some species, such as Amazonian frogs, possess traits that allow them to use the matrix for movement and reproduction, as well as allowing them to tolerate edge effects and survive in the remaining fragments (Gascon et al., 1999).

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE…

Considering the range of impacts, it is unsurprising that the fragmentation of rainforests is one of the greatest threats to global biodiversity (Magnago et al., 2014). And the future does not look bright; as human populations continue to rise, the extent of deforestation and fragmentation of our forests is likely to also increase (Haddad, 2015).

But all is not lost; conservation projects mitigate some negative impacts, with studies discovering types of forest that can reduce edge effects near fragment margins (Mesquita et al., 1999).

BUT WHAT CAN I DO?

Take a look at the following website by Greenpeace and see what you can do to prevent deforestation: http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/forests/solutions-to-deforestation/

[499 words]

References

Bierregaard, R., 2011. Forest fragments under research in the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project. [photograph] Reproduced in: Hance, J., 2011. Lessons from the world’s longest study of rainforest fragments. [online] Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2011/08/lessons-from-the-worlds-longest-study-of-rainforest-fragments/ [Accessed: 21/03/17]

Gascon, C.; Lovejoy, T. E.; Bierregaard, R. O.; Malcolm, J. R.; Stouffer, P. C.; Vasconcelos, H. L.; Laurance, W. F.; Zimmerman, B.; Tocher, M. and Borges, S., 1999. Matrix habitat and species richness in tropical forest remnants. Biological Conservation, 91(2-3), pp. 223-229

Haddad, N. M.; Brudvig, L. A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K. F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R. D.; Lovejoy, T. E.; Sexton, J. O.; Austin, M. P.; Collins, C. D.; Cook, W. M.; Damschen, E. I.; Ewers, R. M.; Foster, B. L.; Jenkins, C. N.; King, A. J.; Laurance, W. F.; Levey, D. J.; Margules, C. R.; Melbourne, B. A.; Nicholls, A. O.; Orrock, J. L.; Song, D. and Townshend, J. R., 2015. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Science Advances, 1(2), pp. 1-9

Laurance, W.F.; Camargo, J. L. C.; Fearnside, P. M.; Lovejoy, T. E.; Williamson, G. B.; Mesquita, R.C.G.; Meyer, C. F. J.; Bobrowiec, P. E. D. and Laurance, S.G.W., 2016. An Amazonian forest and its fragments as a laboratory of global change. pp. 407-440. In: L. Nagy, B. Forsberg, P. Artaxo (eds.) Interactions Between Biosphere, Atmosphere and Human Land Use in the Amazon Basin. Springer (Ecological Studies 227), Berlin, Alemanha.

Magnago, L. F. S.; Edwards, D. P.; Edwards, F. A.; Magrach, A.; Martins, S. V. and Laurance, W. F., 2014. Functional attributes change but functional richness is unchanged after fragmentation of Brazilian Atlantic forests. Journal of Ecology, 102(2), pp. 475-85

Mesquito, R. C. G.; Delamônica, P. and Laurance, W. F., 1999. Effect of surrounding vegetation on edge-related tree mortality in Amazonian forest fragments. Biological Conservation, 91(2-3), pp. 129-134

Niem, Y. Tree frog silhouette. [photograph] Available at: http://fotovenopilon.si/entry/jury/awards.php?section=D [Accessed: 22/03/17]

Ribeiro, M. C.; Metzger, J. P.; Martensen, A. C.; Ponzoni, F. J. and Hirota, M. M., 2009. The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: How much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biological Conservation, 142(6), pp. 1141-1153

Roberts, G., 2016. Cassowary on road. [photograph] Available at: http://sunshinecoastbirds.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/queensland-road-trip-13-etty-bay.html [Accessed: 22/03/17]

Turner, I. M., 1996. Species Loss in Fragments of Tropical Rain Forest: A Review of the Evidence. Journal of Applied Ecology, 33(2), pp. 200-209

Recent Comments