|

Have you ever noticed how much easier it is to breathe on a jog through a luscious park or a woodland compared to the inner city? This is because the air we breathe comes from the photosynthetic process plants provide. In this reaction, plants extract energy from carbon dioxide (CO2) combined with sunlight as well as other organic soil materials and release Oxygen (O2) as a by-product which we then benefit from.

|

Photosynthesis under increasing CO2

Each year since 1959, approximately half of the CO2 emissions we produce linger in our atmosphere (Le Quéré, et al., 2009). With atmospheric levels of CO2 on the rise as a result of our activities, the logical outcome would be that plants have additional CO2 to photosynthesise, allowing for more oxygen for us, right? Indeed, short-term increases have no negative impacts on photosynthesis. In fact, a study suggested they became more efficient at recycling CO2 (Besford, et al., 1990) as demonstrated in the positive feedback photosynthesis and growth of P.cathayana (Zhao, et al., 2012). However, under long-term carbon dioxide exposure, plants lost all photosynthetic gain (Besford, et al., 1990). Other studies have investigated the effects of increasing CO2 levels on plants and it has recently been found that previous models may have overestimated the ability of plant “sinks” to make use of the additional human-related carbon. A “sink” is a location where carbon dioxide accumulates and is absorbed by plants much like running water down a sink.

From carbon sinks to carbon sources

In 1991, Arp projected that plants in the field would not experience a decrease in photosynthetic abilities as a result of atmospheric CO2 increase. However, more recently in 2015, Wieder et al. reported that photosynthetic processes were limited by nutrient availability, in which phosphorus and nitrogen (Aranjuelo, et al., 2013) were the main limiting factors.

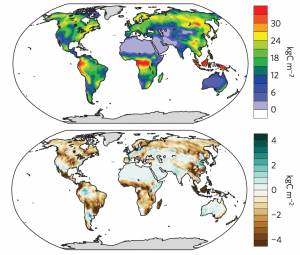

In addition, their models projected that by 2100, plants which were once considered sinks may actually be turning into carbon sources (fig.1). This means they could be emitting more carbon than they absorb as a result of increasing carbon dioxide in the air in combination with the insufficient amounts of other organic materials (nitrogen, phosphorus, minerals, etc.) necessary for photosynthesis and consequently accelerating the rate of climate change which is bad news for us. Plants will essentially be slowly suffocating us as we rely on them for clean air.

A threat to food security

Likewise, as a result of intensifying agriculture, soils are becoming increasingly eroded. For one, this means they are unable to store and process atmospheric carbon as efficiently and there is a lack of nutrients made available to plants (Lal, et al., 2008). This, coupled with the higher concentrations of CO2, poses a great threat to major crop plants such as oilseed rape (Franzaring, et al., 2011) and wheat (Uddling, et al., 2008). In laboratory studies, these crop plants tended to reduce the quality and quantity of their seeds in high concentrations of CO2.

Emissions are not only posing a threat to a plant’s capacity to recycle air but also put our food security at risk.

References

Aranjuelo, I., Cabrerizo, P., Arrese-Igor, C. & Aparicio-Tejo, P., 2013. Pea plant responsiveness under elevated [CO2] is conditioned by the N source (N2 fixation versus NO3 – fertilization). Environmental and Experimental Botany, Volume 95, pp. 34-40.

Arp, W., 1991. Effects of source-sink relations on photosynthetic acclimation to elevated CO2. Plant, Cell and Environment, Volume 14, pp. 869-875.

Besford, R., Ludwig, L. & Withers, A., 1990. The Greenhouse Effect: Acclimation of Tomato Plants Growing in High CO2, Photosynthesis and Ribulose-1, 5-Bisphosphate Carboxylase Protein. Journal of Experimental Botany, 41(8), pp. 925-931.

Franzaring, J., Weller, S., Schmid, I. & Fangmeier, A., 2011. Growth, senescence and water use efficiency of spring oilseed rape (Brassica napus L. cv.Mozart) grown in a factorial combination of nitrogen supply and elevated CO2. Environmental and Experimental Botany, Volume 72, pp. 284-296.

Lal, R. et al., 2008. Soil erosion: a carbon sink or source?. Science, 319(5866), pp. 1040-1042.

Le Quéré, C. et al., 2009. Trends in the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Nature geoscience, 2(12), pp. 831-836.

Uddling, J. et al., 2008. Source-sink balance of wheat determines responsiveness of grain production to increased [CO2] and water supply. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, Volume 127, pp. 215-222.

Wieder, W., Cleveland, C., Smith, W. & Todd-Brown, K., 2015. Future productivity and carbon storage limited by terrestrial nutrient availability. Nature, 8(6), pp. 441-445.

Zhao, H. et al., 2012. Sex-related and stage-dependent source-to-sink transition in Populus cathayana grown at elevated CO2 and elevated temperature. Tree Physiology, Volume 32, pp. 1325-1338.

[486]

Recent Comments