A harsh, cold land with no tree cover, temperatures averaging between -12 to -6 degrees Celsius, and enveloped in snow for the majority of the year (National Geographic, 2017).

Until the brief summer months bring warmth and plains become decorated with swathes of wildflowers. This is the tundra biome.

| Figure 1: Arctic animals |

A home to many endearing (and endangered) animals like the Arctic fox, snowy owl, lemmings and grey-wolves (Figure 1) (National Geographic, 2017). But why should we care about some cold desolate place? The answer is simple yet complicated.

It comes down to the ever looming climate change disaster. The Arctic tundra has been recognised as one of the most vulnerable biomes to environmental change. Permafrost (permanently frozen ground) covers much of the tundra, with the top 30cm or so of it melting and refreezing with the changing seasons (NOAA, 2017). However, in the last few decades increasing global temperatures, and human developments have lead to more melting. This can have a negative effect on the ecosystem as the more permafrost that’s melted, along with the later arrival of the autumn freeze time means that shrubs and other vegetation, that couldn’t take root before, can now grow, potentially altering the habitat (Heijmans et al 2016).

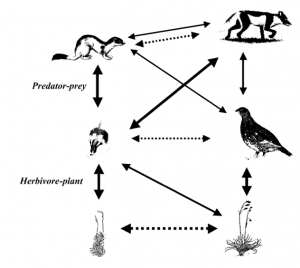

| Figure 2. Different types of interactions within an Arctic tundra ecosystem. Solid lines = consumption between predator and prey between trophic levels (different parts of the food web Dotted lines = interaction between species in the same trophic level (same part of the food web) (Ims and Fuglei, 2005). |

Northward expansion of Low Arctic trees and shrubs has been seen due to the warmer temperatures and longer growing seasons. This has other ecological consequences, like change in the biodiversity of an area if new species are introduced (Post et al., 2009). Overall ecosystem structure change has been recorded in multiple studies, including interaction between animal species (Hobbie et al 2017).

Although they may be cute and fluffy Arctic foxes are one of the key species within Arctic tundra ecosystems because they are a top predator, meaning they help control herbivore populations (Figure 2). It’s been seen that where abandoned Arctic fox dens are found, the productivity of that area (i.e. plant growth, number of insect and herbivores etc.) has increased (Killengreen et al., 2007).

A study by Ims and Fuglei, (2005) has shown that lemmings are also key players in the Arctic tundra. These rodents are a key prey species for a number of predators that rely on certain densities of lemming populations to allow them to reproduce, as they need sufficient amount of food. Lemmings breed during the winter season and undergo growth under the snow, leading to a peak in population density in spring. This means that with predicted warmer winters (hence less snow, and more rain) lemming peak times are very likely to alter, with population peaks happening during autumn (Putkonen and Roe, 2003). A change in the number of prey available, will impact predator numbers. Arctic fox and snowy owl numbers are likely to decrease as they will have lower reproductive rates during years when peak lemming populations occur autumn.

A change in the relationships between key species like this can have unprecedented effects on their communities and ecosystems. With a grim future ahead for cold-loving animals and ecosystems.

References

National Geographic, (2017). Explore the World’s Tundra. Available at: http://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/tundra-biome/ [Accessed 17 Mar. 2017].

NOAA (2017). Arctic Change – Land: Permafrost. Available at: https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/arctic-zone/detect/land-permafrost.shtml [Accessed 17 Mar. 2017].

Post, E., Forchhammer, M. C., Bret-Harte, M. S., Callaghan, T. V., Christensen, T. R., Elberling, B., … & Ims, R. A. (2009). Ecological dynamics across the Arctic associated with recent climate change. Science, 325(5946), 1355-1358.

Ims, R. A., & Fuglei, E. V. A. (2005). Trophic interaction cycles in tundra ecosystems and the impact of climate change. Bioscience, 55(4), 311-322.

Killengreen, S. T., Ims, R. A., Yoccoz, N. G., Bråthen, K. A., Henden, J. A., & Schott, T. (2007). Structural characteristics of a low Arctic tundra ecosystem and the retreat of the Arctic fox. Biological Conservation, 135(4), 459-472.

Putkonen J, Roe G. 2003. Rain-on-snow events impact soil temperatures and affect ungulate survival. Geophysical Research Letters 30: 1188.

Heijmans, M. M. P. D., van Huissteden, J., Li, B., Wang, P., Limpens, J., Berendse, F., & Maximov, T. C. (2016). Can wet summers trigger permafrost collapse at a Siberian lowland tundra site?. INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON PERMAFROST, 2016-06-20/2016-06-24

Hobbie, J. E., Shaver, G. R., Rastetter, E. B., Cherry, J. E., Goetz, S. J., Guay, K. C., … & Kling, G. W. (2017). Ecosystem responses to climate change at a Low Arctic and a High Arctic long-term research site. Ambio, 46(1), 160-173.

Word count [496]

Recent Comments