British food security is under threat due to Climate change.

If you haven’t heard of ‘climate change’ you‘ve either been living under a rock for the last 30 years or getting yourself elected as leader the free world. But not much has changed, Winter’s a little warmer, summer’s a little wetter? We’ve heard of extreme weather conditions in some far corners of the globe but unless you’ve been planning a trip there, it’s unlikely to affect our everyday lives. But behind supermarkets sliding doors lurks a real peril, one directly impacting Britons at their most vulnerable part, our Achilles heel, our pockets. As crop production is jeopardised, already inflated prices are set to rise, correlating with the environmental changes induced by human pollution (Lobell, 2007).

Food security is perhaps the most important commodity provided by the planet. At a glance the effects of climate change, seem on the whole, to be exactly what farmers are looking for in terms of improving yield from their crops. It’s wet, hot, there’s more CO2, more decomposition and available nutrients, just what plants need right? But this is not always the case, although higher CO2 levels does stimulate plant growth, it is counteracted by the increase in temperature and ozone, a molecule with harmful effects on plant tissue(Hogsett, et al 1997). Warming decreases the quality of the crops produced, grains are less dense and seeds contain less oil, as well as favouring growth and proliferation of weeds into new areas, due to the differences in how they photosynthesise (Fuhrer, 2003. Martre, 2017).

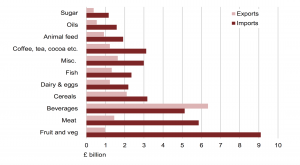

It is no secret that as a nation we currently import almost half of our food and animal feed from overseas (Ruiter et al 2015). In response to huge population increases of 3 Million on average every decade since the baby boomers of the 50s(Humby, 2016) and market for year-round exotic produce. But tropical regions are likely to suffer much more, even a slight temperature increase interfering with developmental and growth processes beyond already stretched thresholds, meaning production in these areas will fall hugely(Challinor, 2008). Excess precipitation, effectively drowning roots and drought adding another uncertain dimension to the mix(Amedie, 2013).

“[In staples like wheat, maize and barley] warming has resulted in annual combined losses of $5 billion per year, as of 2002” -Lobell, 2007

Environmental change is going to effect everyone in one way or another, we rely on plants for food, clothing, oxygen, medicine and much more. Prices of everyday commodities reflect the quantity and quality of production processes. The result is innumerable aspects of our lives being changed, in some way by the unsustainable practices we are complicit to on a daily basis(Lepetz et al., 2009).

Research into genetic modification of crop plants provides some relief in the challenges ahead, improving crop plant coping mechanisms and yield potential (Martre et al 2017), as well as a decrease in the consumption of animal products due to their high carbon footprint and inefficiency(Ruiter et al 2015). For now it will be a 4p increase in a farmhouse loaf and 10p extra for sunflower oil, but immediate action is necessary to prevent a large-scale food shortage in the near future.

[500 words]

References:

Amedie, F.A., (2013). Impacts of Climate Change on Plant Growth, Ecosystem Services, Biodiversity, and Potential Adaptation Measure. , pp.1–61.

Challinor, A.J. & Wheeler, T.R., (2008). Crop yield reduction in the tropics under climate change: Processes and uncertainties. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 148(3), pp.343–356.

Fuhrer, J., (2003). Agroecosystem responses to combinations of elevated CO2, ozone, and global climate change. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 97(1–3), pp.1–20.

Hogsett, W.E., J.E. Weber, D. Tingey, A. Herstrom, E.H. Lee and J.A. Laurence. (1997). An approach for characterizing tropospheric ozone risk to forests. Environmental Management 21:105-120.

Humby, P. (2016). Overview of the UK population: February 2016. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/february2016. [Accessed 13 March 2017].

Lepetz V., Massot, M. & Schmeller, D.S., & Clobert, J., (2009). Biodiversity monitoring: some proposals to adequately study species’ responses to climate change. Biodiversity and Conservation 18, 3185- 3203

Lobell, D.B. & Field, C.B., (2007). Global scale climate–crop yield relationships and the impacts of recent warming. Environmental Research Letters, 2(1), p.14002.

Martre, P., Yin, X. & Ewert, F., (2017). Modeling crops from genotype to phenotype in a changing climate. Field Crops Research, 202, pp.1–4. Available at: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378429017300242.

Ruiter, H. de et al., (2015). Global cropland and greenhouse gas impacts of UK food supply are increasingly located overseas. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 13(114). Available at: http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/13/114/20151001.abstract.

WordShore (flickr), (2016), Fruit (WordShore)[ONLINE]. Available at: https://hiveminer.com/Tags/hebrides,solas [Accessed 15 March 2017].

Recent Comments